Chapter 4

Agnar Helgason, drawing on Iceland population records, demonstrates higher fertility with closer kinship.

We are in pursuit of whatever makes inbreeding kill babies, because it does not stop there. We have seen that the mechanism is inherited but not genetic and it stabilizes a population at some moderate size, neither too small to survive nor too large. We have seen the Sibly curve, which is supported by massive amounts of data, which shows the mechanism in effect, stabilizing populations of mammals, birds, fish and insects. It would be understandable for a prudent person so say, “Ah, but those are all dumb animals. We humans choose whether to reproduce.” And to a degree we can, but we need to look at some human data.

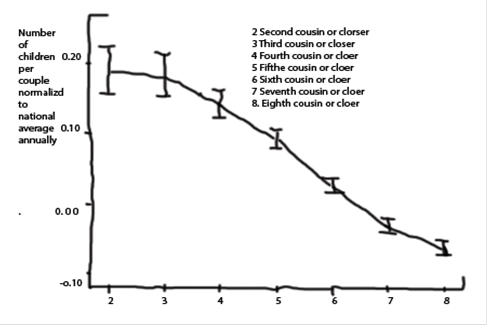

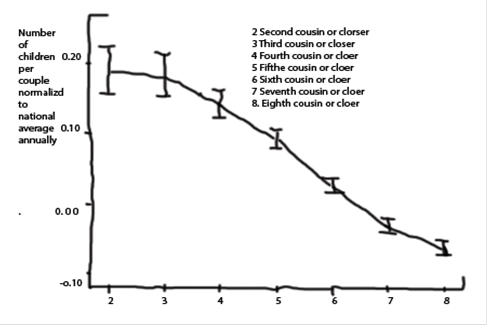

A team led by a man named Helgason looked at data from the enormous Icelandic genealogy. Then he compared the kinship of couples with how many children they had. This is what he got:

Fertility on the vertical axis. Kinship (by their own non-standard measure) on the horizontal axis.

Fig. 21 3

Gaze at it a bit and then let me tell you what they have done. They chose a large number of couples. They recorded the number of children each pair had. They calculated the kinship of the couples by going back ten generations and counting how many ancestors they shared in that generation. Then they calculated kinship in terms of say first cousin if they shared a quarter of the possible number of ancestors, second cousin if they shared an eighth and so forth. Obviously, this is not the way we ordinarily recon kinship. I’m sure very few can name all their ancestors for 10 generations back. Then they lumped the data so that every couple between say third cousin and fourth cousin was labeled “fourth cousin or closer.” I might have suggested “third cousin once removed.”

Then they took the average number of children in each fraction and “normalized” it, which means they compared it with the average across the country for that year. Thus, zero means the same degree of fertility as the Icelandic average (I think).

We can immediately recognize the Sibly curve. Do not think for a second that humans are exempt. The effect is not enormous, going from roughly 5% below to 20% above the national mean, but the effect is clearly not trivial.

Now look at the error bars. They are very tight. Those are ninety five percent confidence limits. There cannot be much else determining fertility. Any factor other than kinship of the couple has to squeeze into that little interval. That includes choice. It will be more extreme when we look at the next generation.

Before that, however, look at “eighth cousins or closer.” That is the most distant relationship they examine. Either they have thrown away data on ninth cousins, remembering that this is their way of calculating, which are vanishingly rare or totally absent. That alone should give a prudent person a maximal warning.

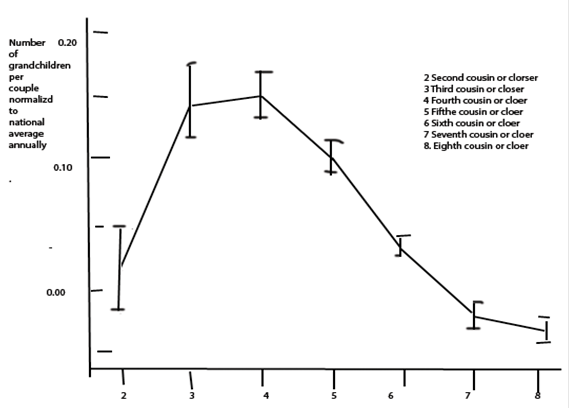

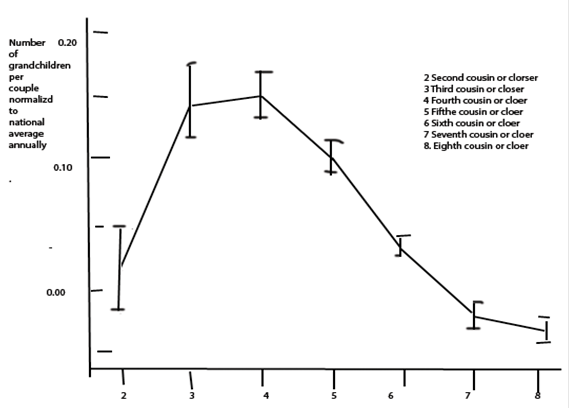

Helgason’s team went further and looked at the next generation, the grandchildren:

Number of grandchildren is on the vertical axis. Kinship, by their reckoning, is on the horizontal.

Fig. 224

The axes are about the same. Vertical axis ranges from a little below the Iceland average to 15% above. Thus, in only two generations the kinship choices can change fertility quite substantially. The horizontal axis is “second cousin or closer,” then “third cousin or closer” and so forth.

Notice that while “second cousins or closer” gave the greatest number of children, it does not give the greatest number of grandchildren. To my eye, third cousins should have the most grandchildren. Don’t start muttering “inbreeding depression” just yet. First cousin once removed still produces more grandchildren than does anything more distant than about 6th cousin, which is close to “zero” or the Iceland average, and which I would guess to be reasonably close to replacement.

Since there is no reason to expect a couple to have exactly the same kinship as their respective parents, much of the variation in the number of children a couple might have (remember the 95% confidence limits) must be due to the kinship of the parents. On the face of it, fertility in that country is due to kinship issues AND NOTHING ELSE. Maybe you can choose your mate, but that choice having been made, the number of children cannot be changed. It remains moot whether a couple can move the timing of their children about. So helpful government intervention, like providing free baby sitting for working mothers, might result in a short-term increase in the number of births, but that might just mean couples were having their babies earlier without changing the number at the end of the day.

We shall see later that people and mice, most likely mate for status and not attraction. If that is the case, it is obviously lamentable, since the best choice on the basis of status quite likely is not so close a relative as if the choice were made on the basis of attraction; since closer kinship, within limits, results in greater fertility, one would expect that natural selection would tend to hardwire in an attraction to closer cousins.

We shall also see, later, that folic acid supplement can affect fertility, but for now the evidence at hand only supports the concept that kinship issues absolutely determine fertility.

So that is the heart of the chapter: kinship determines fertility for humans just as it does for other animals.

Now, let us think about the mechanism for a moment. I said that for our purposes a baby begins when the sperm touches the egg. The combination is called a zygote. The term refers to a yoke of oxen. If you are using oxen to pull your cart or plow your field, you might be well advised to use two oxen with a single yoke. This means that they are compelled to work together as a team. A single ox might have no great interest in understanding what you want and not be cooperative. The yoke means one cannot wander off to take an interest in a nice-looking blade of grass. I don’t know. I’ve never worked with oxen.

We generally break infertility down into pre-zygotic and post-zygotic infertility. Pre-zygotic infertility refers to the loss of a baby because even though egg met sperm, they failed to get together and form a zygote, which then would in all expectation undergo a large number of cell divisions to produce the placenta and umbilical cord and a fetus, leading after a few months to a brand new red squaller. Anything that prevents the baby from developing so far, or prevents the further development, socialization, romance and finally producing an egg or a sperm to reach a contribution from the opposite sex, that is all post-zygotic infertility.

Back when I was active in diagnostic radiology, I would occasionally be asked to perform a procedure called a hysterosalpingogram. There were a number of indications, but the great majority were because of infertility in a couple who had been studied every other way and were normal.

The woman would be positioned on a table, draped and her feet put in stirrups so she could get her knees apart. Using clean technique, you would get access to her birth canal with a speculum, visualize the cervix and then take the tenaculum. It is an instrument sort of like a long pair of scissors without the sharp edges but with rather alarming looking opposed hooks at the ends. Don’t give it a second thought. This is a woman who intends to get pregnant. A starving wolverine might be willing to negotiate over a hunk of meat, but if a woman is trying to have a baby, don’t get in the way. You are looking at nerves of steel with the full backing of society. So, without cringing, you hook the cervix low and to one side and tug. The cervix is not sensitive, you keep whispering to yourself. Then you take the acorn cannula, which is a round, tapered device with a tube down the middle, and insert it into the cervix. If you are a coward, you can just visualize the cervix and insert a little tube with a balloon on the end, and inflate the balloon within the uterus. That will mean you cannot see the endocervical canal, and you could miss a small tumor. If you are willing to leave a cancer in an otherwise healthy young woman because of your own compunctions, please perform seppuku right away.

You inject contrast material and get x-ray images. If it is abnormal, you know before you look at the patient because the surgeon will be there to make sure he gets the information he needs. The rest of the time it will be normal, not just pretty good but spectacularly good. This is where selection places its prime interest.

Glancing back at the graph of number of children against kinship, you see that there is no inbreeding depression. This is fertility consequent to inheritance, so it is epigenetic. It is occurring in the first generation, so it is pre-zygotic. If the zygote splits a couple of times before giving up, that is as post-zygotic as if I cannot meet the emotional needs of a woman and wind up an ancient bachelor. So, we can say with certainty that there is at least a pre-zygotic, epigenetic mechanism that reduces fertility as you go to less and less kinship than second cousin, bearing in mind their unique way of reckoning kinship.

Now on to the graph of number of grandchildren against kinship, the “second cousin or closer” cohort have fewer babies than the “third cousin or closer fraction.” There is your inbreeding depression. Oh, it’s not as bad as trying to have babies with an 8th cousin, by no means, but it is less than it might be with some middling degree of kinship. So, we can again say with conviction, there is also a post-zygotic, epigenetic mechanism that causes infertility in humans.

So, there is our source of inbreeding depression. It is a side-effect of the mechanism that helps limit population size by reducing fertility when kinship is sub-optimal. Think about it. Suppose your have a population that falls on hard times until the number of members are countable on the fingers on one hand. In that case, the last thing the population needs is inbreeding depression. But that is precisely what happens.

Think about it. Selection has given animals a route to extinction. I shall not go so far as to say there is no escape at all. Suitable mutations might indeed shut down the post-zygotic mechanism, since it arose by mutations in the first place. But that would unleash, when times improved, unlimited growth, or at least growth limited only by pre-zygotic infertility. The population would be doomed because it would increase until speciation effects produced absolute infertility, and the population would be doomed anyway. Shut down the speciation effects, and the population could in the long run be unable to adapt to niches as fast as normally speciating populations, and doom lurks again.

We have now accomplished our initial purpose. We know why inbreeding kills babies; it is an epigenetic, post-zygotic mechanism and maybe pre-zygotic. And we know why: the overwhelming need to restrict population size in order to remain nimble in the competition for new niches requires it.

Later we shall run the mechanism all the way to the ground. We shall be able to see how it works down to the biochemical/microbiological level. But there are many lines of evidence to adduce first. To begin with, we will look at data coming from Denmark supporting the Iceland experience. Both of these are prosperous advanced societies. If a woman in either country wants to have a baby, there will be no social resistance, and the baby can expect to have a most comfortable and enviable life. This may have something to do with how clean the numbers are. I cannot swear that less blessed lands might not have messier data.

There are Icelanders in Iceland and, among others, Lugbara in Uganda. There are differences, and how important any one difference might be could usually be a matter of debate. But where it really counts, the supremely important issue, is fertility. A glance at page 30 will remind you that maximum grandchildren come with third cousin marriages. Lugbaras divide themselves into tiny clans, and a man may not marry a girl from his own clan, nor that of either of his parents, this probation lasting three generations. 5 Yep, fourth cousin is fine, or a little less kin – among these tightly held families finding a suitable mate out at 10th cousin is unlikely. In short, both the Icelanders with their thousand-year genealogy and sophisticated computer analysis and elders among the Lugbara come up with the identical answer. The Lugbara want to maximize grandchildren, their work being hard and their land fertile; women do all the work in this society except the men do land clearing and maintain irrigation ditches. Children, like children everywhere, take more supervision than they accomplish.

Chapter 5

Table of contents

Home page.